Most ebook files are in PDF format, so you can easily read them using various software such as Foxit Reader or directly on the Google Chrome browser.

Some ebook files are released by publishers in other formats such as .awz, .mobi, .epub, .fb2, etc. You may need to install specific software to read these formats on mobile/PC, such as Calibre.

Please read the tutorial at this link: https://ebookbell.com/faq

We offer FREE conversion to the popular formats you request; however, this may take some time. Therefore, right after payment, please email us, and we will try to provide the service as quickly as possible.

For some exceptional file formats or broken links (if any), please refrain from opening any disputes. Instead, email us first, and we will try to assist within a maximum of 6 hours.

EbookBell Team

4.7

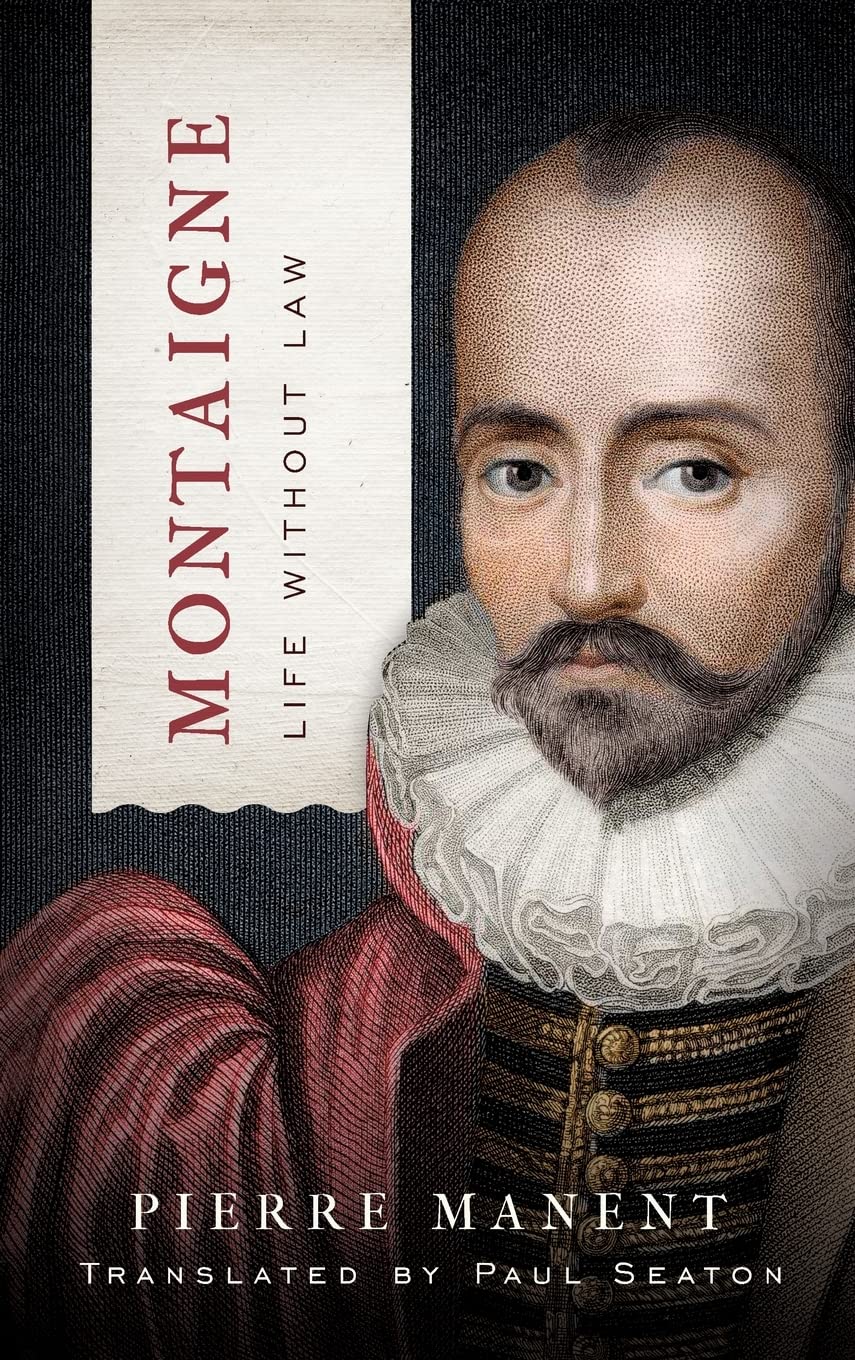

76 reviewsIn Montaigne: Life without Law, originally published in French in 2014 and now translated for the first time into English by Paul Seaton, Pierre Manent provides a careful reading of Montaigne’s three-volume work, Essays. Although Montaigne’s writing resists easy analysis―Montaigne includes seven essays before he even explicitly states the purpose of the Essays―Manent finds in it a subtle unity, and demonstrates both the philosophical depth of Montaigne’s reflections and the distinctive and even radical character of his central ideas.

To show Montaigne’s unique contribution to political discourse, Manent compares his work to other influential modern philosophers, including Machiavelli, Hobbes, Pascal, and Rousseau. For example, whereas Hobbes proposed the modern state as necessary because of humanity's supposedly natural condition in a “war of all against all,” Montaigne did not see the state as the remedy to civil-religious discord. But in fact, speculation on the state does not play a large role in the Essays. Rather, Montaigne’s philosophical reflection focuses on the concept of what he calls la condition humaine, the human condition. In Montaigne: Life without Law, Manent tracks how Montaigne develops this concept. Above all, Manent encompasses Montaigne’s analysis in three terms: virtue, pleasure, and death. As Manent shows, by deploying these and other categories, Montaigne’s Essays present not a philosophical system, but rather a new form of thinking and living, which provides us with a way of engaging in a truly thoughtful life.

What might human life look like without the imposing and even towering presence of the state? In raising this critical question, Montaigne’s Essays makes an important inquiry that remains of great relevance for Europe and other areas of the world alike.